The History of the Futon Frame and Futon Mattress

The futon, a staple of minimalist design and multifunctional living, has a long and fascinating history. Its journey from traditional Japanese bedding to a modern global home furnishing reveals much about evolving lifestyles, design trends, and cultural exchange. To understand the full story of the futon, it is important to explore the origins of both the futon mattress and the futon frame — two components that have developed both independently and in tandem over centuries.

Origins in Japan: The Traditional Futon

The futon's history begins in Japan, centuries ago, where the term “futon” originally referred to a simple, foldable mattress placed directly on a woven straw tatami mat. The word "futon" in Japanese (布団) literally means "round cushion," although the form we recognize today is rectangular. Traditional Japanese futons are composed of two parts: the shikibuton (the mattress) and the kakebuton (the duvet or comforter). Sometimes a makura (pillow) filled with buckwheat husks completes the set.

Historically, bedding was a luxury in Japan. In the Heian period (794–1185), the wealthier classes used bedding stuffed with natural materials like straw or cotton, while commoners often slept directly on tatami mats with a simple blanket. Cotton, a key material for futons, wasn’t widely available until the Edo period (1603–1868), when it became more accessible due to domestic production and trade. By the 18th century, futons were widespread across Japanese households.

The traditional futon was valued for its simplicity, space-saving nature, and compatibility with Japanese homes, which often had limited space and multifunctional rooms. During the day, futons could be folded and stored in a closet (oshiire), freeing up room for daily activities.

Western Adaptation: The Evolution of the Futon Frame

The Japanese futon remained relatively unchanged until the 20th century, when it caught the attention of designers and cultural enthusiasts in the West. After World War II, American soldiers stationed in Japan brought home tales of Japanese minimalism and efficient use of space. These stories, coupled with the post-war boom in international travel and interest in Eastern philosophy, introduced many Westerners to Japanese design principles.

In the 1970s, as interest in Eastern lifestyles surged — influenced in part by the counterculture movement and a desire for more sustainable, less materialistic living — the futon began appearing in the United States and Europe. However, the Western version of the futon quickly diverged from its Japanese predecessor.

Western homes typically had carpeted floors and different heating systems than Japanese homes, making it less practical to sleep directly on the floor. To adapt, designers created the futon frame — a wooden or metal base that elevated the mattress off the floor and often folded into a sofa. This innovation aligned with Western preferences for off-the-floor sleeping arrangements and dual-purpose furniture. The futon frame became especially popular in college dorms, small apartments, and urban homes where space was at a premium.

Materials and Manufacturing

In traditional Japan, futon mattresses were handmade and filled with cotton. They were beaten regularly with a bamboo stick (futon-tataki) to keep them fluffy and aired outdoors to avoid mold and insects. Western futons, however, were typically mass-produced and used a wider range of materials. Foam, innerspring coils, and synthetic fibers were added to provide extra support and longevity.

Futon frames also varied widely in style and function. Some were simple, foldable wooden slats, while others included convertible mechanisms, drawers for storage, or elaborate designs. The most common types included the bi-fold frame, which folded once to form a couch, and the tri-fold frame, which folded twice and allowed for more flexible positioning.

The Futon Boom in the U.S.

In the 1980s and 1990s, futons experienced a boom in popularity in the U.S. Companies like The Futon Shop and others promoted them as healthy, natural alternatives to traditional mattresses. They appealed to the eco-conscious market as well as young adults setting up their first homes.

Futons were marketed as versatile, affordable, and practical — ideal for guests, small spaces, or anyone seeking a non-traditional sleep experience. Some manufacturers also emphasized the use of organic cotton and chemical-free construction, tapping into a growing wellness trend.

As futons gained popularity, their image evolved. While once seen as bohemian or alternative, they gradually became mainstream. However, this rise was not without challenges. Many consumers found that inexpensive futons lacked durability or support, especially when used as a primary bed. Over time, futons became associated more with temporary or student furniture, rather than a long-term sleep solution.

Modern Trends and Global Influence

Today, the futon continues to evolve. In Japan, many people still use the traditional shikibuton, particularly in smaller apartments or for guest accommodations. Modern Japanese futons have improved in materials and comfort, with some even featuring memory foam or modular components. They remain easy to store and ideal for multipurpose rooms.

In the West, futon frames and mattresses are now available in a wide range of styles and price points. Luxury futons with thick, multi-layered mattresses and elegant frames can rival traditional beds in comfort. The rise of minimalist and space-saving living — driven by trends like tiny homes, van life, and modular furniture — has renewed interest in futons as a practical choice for modern living.

Additionally, the global focus on sustainability has led to a resurgence of natural-fiber futons made with organic cotton, wool, or latex. These products reflect a return to the futon’s roots while integrating contemporary values like environmental responsibility and wellness.

Cultural Symbolism

Beyond its physical form, the futon holds symbolic meaning. In Japan, it represents simplicity, impermanence, and respect for space — key tenets of traditional Japanese aesthetics and Zen philosophy. The act of folding and storing a futon each morning is both practical and reflective, aligning with the concept of ma, or the intentional use of empty space.

In the West, the futon has come to represent flexibility, transitional living, and a more casual lifestyle. It is often associated with students, young professionals, or those who prioritize adaptability in their living space.

Conclusion

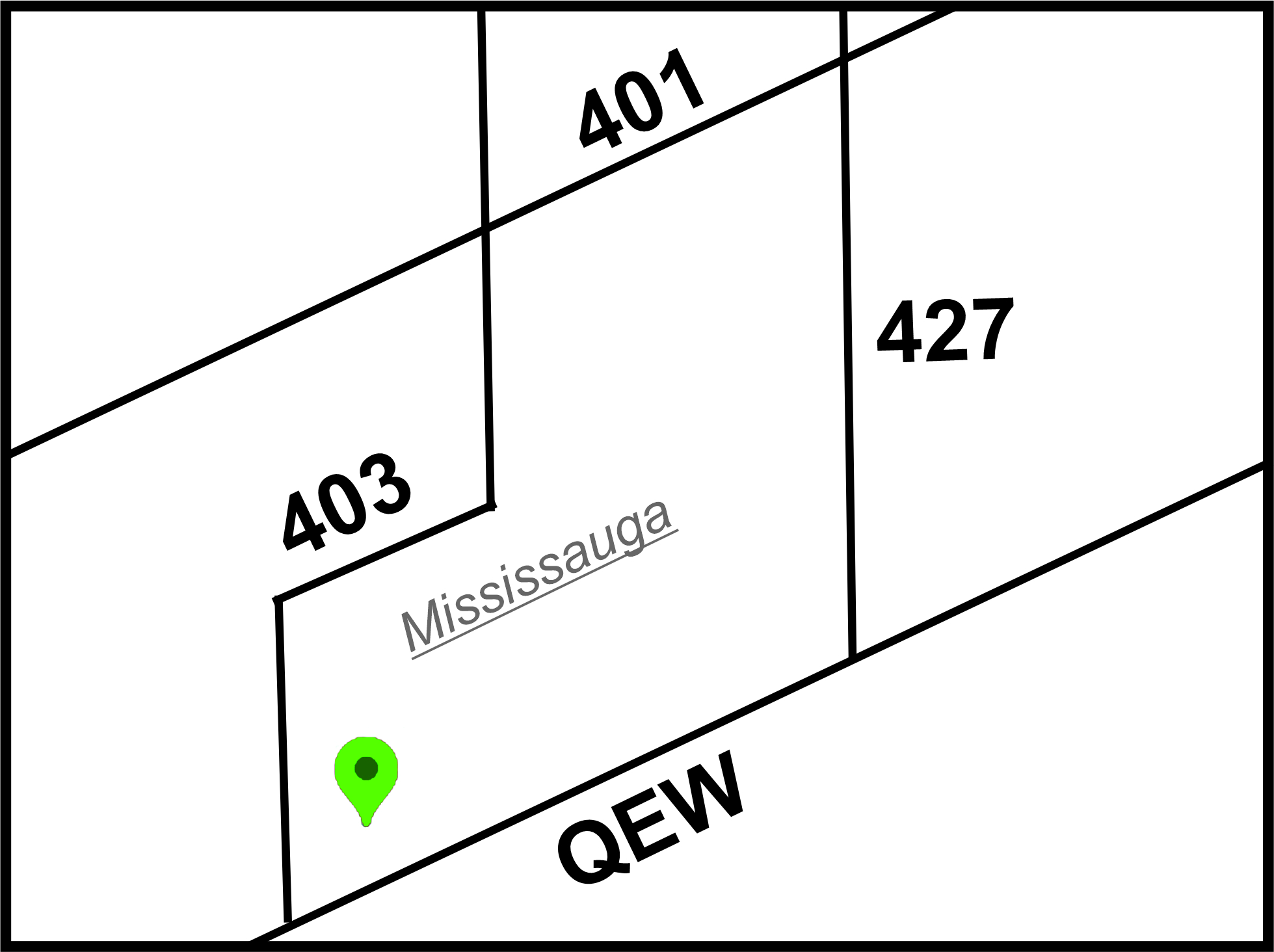

The history of the futon is a story of adaptation and transformation. From hand-stitched cotton mats on tatami floors in Edo-era Japan to foldable couches in Toronto apartments, the futon has proven its enduring value. While its form has shifted across cultures and decades, its core principles — simplicity, versatility, and space-conscious design — continue to resonate in our ever-changing world. As modern lifestyles continue to embrace multifunctionality and minimalism, the humble futon remains a timeless companion in the pursuit of smart, stylish living.

Copyright © 2025 |

Copyright © 2025 |